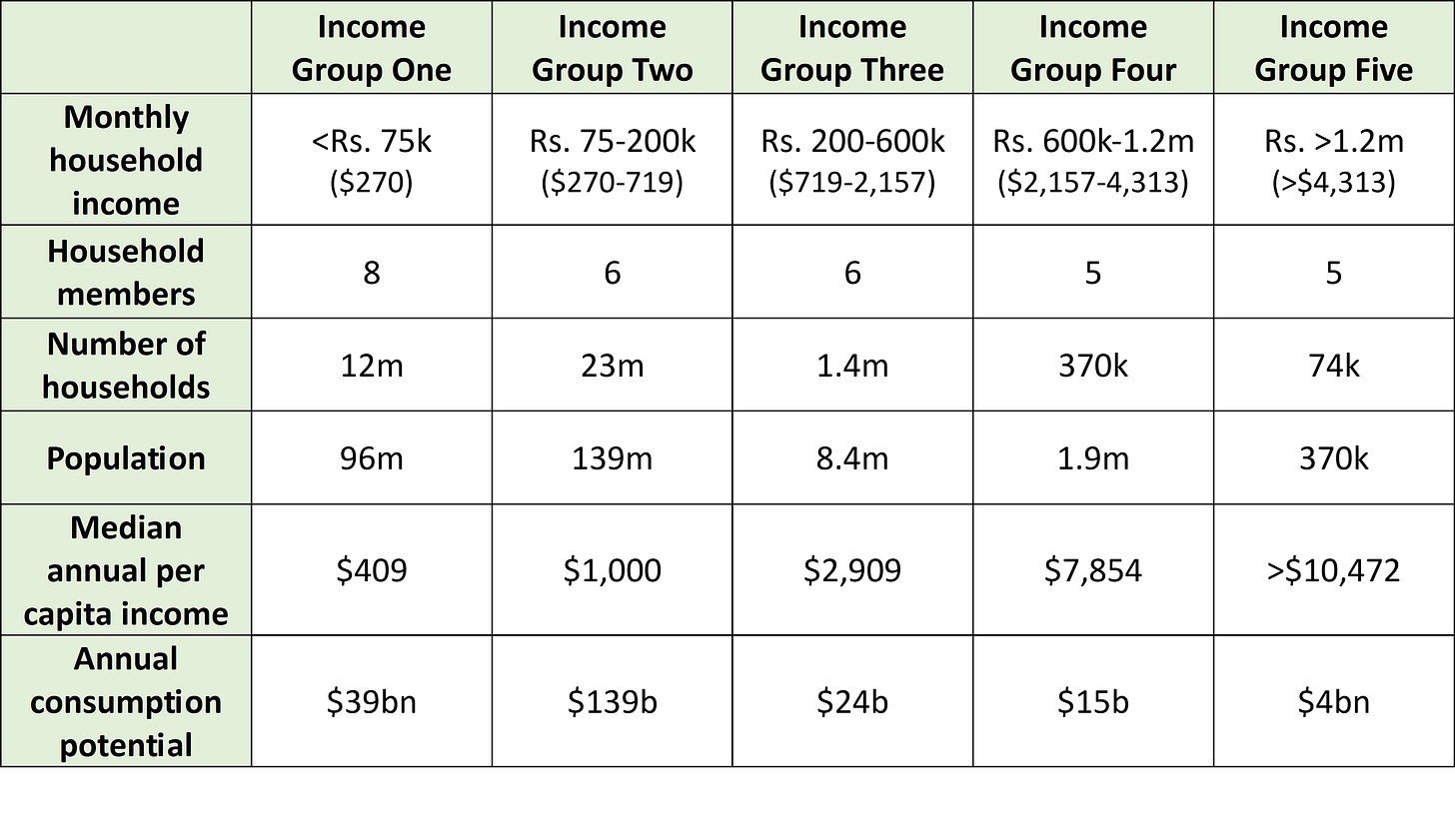

It is the first thing on everyone’s presentation about Pakistan – 250m population!! Who wouldn’t be impressed by such a large number of potential customers? While undoubtedly impressive, this number alone does not tell the whole story. Size matters, but in this case it is important to understand the breakdown of the 37m households and incomes within that population to identify the correct business models and strategies to pursue. This blog post is an extension of work that Sturgeon Capital carried out as part of our due diligence on an opportunity in Pakistan. It is based on our experience, multiple conversations in the ecosystem and latest economic surveys of Pakistan.

Population & consumption breakdown

32.53% of households exist below the poverty line with a household income below Rs. 75,000 per month. These households are extremely price sensitive and time insensitive. The journey towards truly having any monetizable use-case for this group will require decades of structural changes for them to be included as a large enough market to serve. This is the labour class of Pakistan, who can be lifted out of poverty but only when there is a social safety net created. The upper-quartile of this class are expected to join the lower quartile of the new emerging lower middle class, as discussed below, in the next decade. Migration to the GCC and other more developed markets is a trend to monitor that can catapult this class into the lower middle class faster than expected.

62.46% of households generate an income between Rs. 75,000 to 200,000 per month. These households are very price sensitive and partially time sensitive. This is the silent majority or the bulk of where people fall in the country, with the likes of Daraz and Bykea targeting households in the upper quartile of this range. This market is expected to experience the greatest level of upward mobility over the next 10 years, with average income per capita expected to rise at least 25% and up to 40%. This is the long-tail of the Pakistani consumer market.

3.8% of households generate an income between Rs. 200,000 to Rs. 600,000 per month. These households range from price sensitive to very price sensitive and partially time sensitive to very time sensitive. This can also be called the upper middle class of Pakistan, which has part-time drivers and maids, but focus their spending on education, investments and travel. They are also discount driven and prudent with their expenditure but have generally at least 2 members of the household working, thus require a high level of convenience as well. This group generally frequents more upscale grocery stores and only buys branded products. They are also more private in nature but aspirational at the same time so tend to be the ones who time their online purchases with sales but hardly ever in a group purchasing model. This is the core market for Bykea, Daraz, FoodPanda and formerly Airlift. The medium term opportunity in this group is to tap into the Gen Z component, who are more social and interested in gamification and non-monetary value.

1% of households generate an income between Rs. 600,000 to Rs. 1,200,000 per month. These households range from partially price sensitive to price sensitive and time sensitive to very time sensitive. The caveat being that these households have drivers, maids and other hired help which perform most tasks and chores, therefore an activity outsourcing model is hardly ever utilized. They also prefer to shop in store because of a more personalized offline shopping experience, however the younger/more digitally savvy members of this group increasingly prefer to shop online. This is the most immediately monetizable userbase in Pakistan but are extremely brand sensitive and are more individualistic than others, therefore spending their money on Quick Commerce, D2C brands, fast-fashion and branded electronics. This is where most of the discount driven marketing dollars go and is the ideal customer base for banks, quick commerce, premium brands and boutiques. Half of this population is skewed into their early 50s and above, therefore any high CAC spend is an investment in the wrong user. Brands have caught on and are now targeting younger members of this group with activity driven incentives, e.g. FoodPanda being at the forefront through transitioning from a debit card discount model to an activity based voucher model as the primary rewards mechanism. Most e-commerce brands target this population with content marketing to generate non-sales led revenue.

0.2% of households generate an income above Rs. 1,200,000 per month. They are neither price nor time sensitive and live a very sheltered lifestyle compared to the rest of the population. This can be called the ultra-wealthy population when measured on a PPE and per capita basis. These households are the iPhone and X/Twitter users of Pakistan but are demographically skewed to be much older, with fewer young people, and a focus on premium online stores, which in effect means buying imported products such as M&S olive oil and Huda Beauty foundation at eye-gouging premiums. Extremely brand conscious and private by necessity, they rarely shop in the country and mostly seek lifestyle/ultra-luxury brands.

Conclusions

When we look at consumer segments in Pakistan from a socio-economic angle, measuring both household consumption potential and per capita income it is clear that we must think about individual and collective consumption models in a different way.

Take for example Income Group One. Although the collective consumption of this group is significant due to having close to 100m people, from a per-capita income perspective it lacks consistent discretionary purchasing power. This is significant for two reasons: a) sub-par repeat purchase/AOVs resulting in b) long CAC payback periods. This makes performance marketing-based growth strategies extremely low ROI vs. organic/content led.

A successful model to cater to these users requires a collectivist consumption approach that has some form of individual cash-flow improvement characteristics. This can be in the form of a) commissions and b) bulk discounts. That being said, time is a friend for many developing markets where inflation and real-wages start adjusting to improve base income levels, which means timing is an important consideration when it comes to implementing models at scale.

When we look at Income Groups 2 and 3, there is enough collective spending power and an improved per capita income that enables a larger variety of SKUs to be consumed. However, we do not expect this group to be ultimately high ROI unless the same collectivist acquisition strategy is implemented, again leveraging commission and bulk discounts. What is important is that the base education and income levels and digital adoption in these groups should show clear and rapid upward mobility. CAC payback periods should be shorter than a year and on a 10 year spectrum a significant ROI can be generated from each user, with better GMV retention over time in the absence of significant competition.

The top half of Group 3, along with Groups 4 and 5, is what we would call the immediately addressable user base, who are attracted to premiumization, productivity hacks and have individualistic buying behaviours on top of a collectivist buying behaviours. Think about these groups as almost one social block that is trend driven, with complex socio-economic signalling behaviours. Fashion and Beauty marketplaces are likely to do well within this socio-economic group, along with embedded consumer credit enabling larger purchases for Electronics marketplaces. In many ways this group is no different than middle-income country consumers, from a discretionary buying behaviour stand-point. The key thing to understand is that this consumer segment is likely to power high levels of GMV growth early and moderate levels of profitable growth, because of higher levels of churn due to both offline and online competition.

It is also important to think about how homogeneous consumption shapes up in the form of trends, which means business models that can curate and fulfil trends better than others are likely to have the Group 3, 4 and 5 as patrons. It is likely that just like the offline economy in Pakistan, the online economy may also be fragmented but much less so. The fragmentation is driven by varying levels of customer segmentation and price discrimination, powered by a growing local supply-chain. Focus and localization will ultimately drive success in this scenario and vertical marketplaces/e-commerce enablement platforms may be the winners.

Where does that leave the magical 250m population figure in reality? For many business models, especially those which are common in more developed markets, the real addressable market is perhaps only 10.6m if we include all of Groups 3, 4, and 5. While still a $43bn opportunity, if we factor in the propensity and ability of different ages within those groups to adopt technology, the number may be only half of that. To build a scalable consumer-focused business in a market like Pakistan requires novel business models and go to market strategies that must be highly localised to succeed.